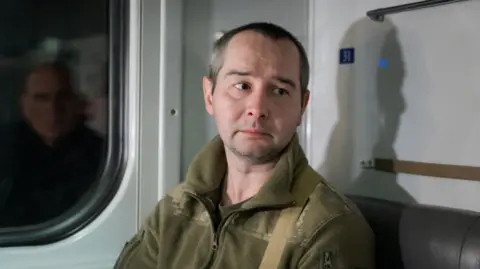

Propped up in her hospital bed, railway conductor Olha Zolotova speaks slowly and quietly as she talks about the day her train was hit by a Russian drone.

When the Shahed [drone] hit I was covered in rubble. I was in the second car. People pulled me out, she says.

My eyes went dark. There was fire everywhere, everything was burning, my hair caught fire a little. I was trapped.

Olha is a victim of Russia's increasingly frequent attacks on the Ukrainian railway system – vital infrastructure that keeps the country moving three and a half years since Moscow's full-scale invasion.

Ukraine's 21,000km-long (13,000-mile) railway system is not merely a mode of transport, it is a central pillar of Ukraine's war effort and a powerful national symbol of resilience.

Olha's injuries were severe, so she was transported more than 300km (185 miles) to a special hospital in the capital, Kyiv, dedicated to railway workers.

Her train was hit earlier this month at a station in Shostka in the northern Sumy region.

As rescue workers sought to tend to the injured, a second Russian drone struck the station – a type of hit known as a double tap.

Ukraine says civilians and rescue teams were directly targeted, which would constitute a possible war crime under international law.

Thirty people in total were hurt. Of those treated in hospital, three were children, and one man was found dead, possibly from a heart attack.

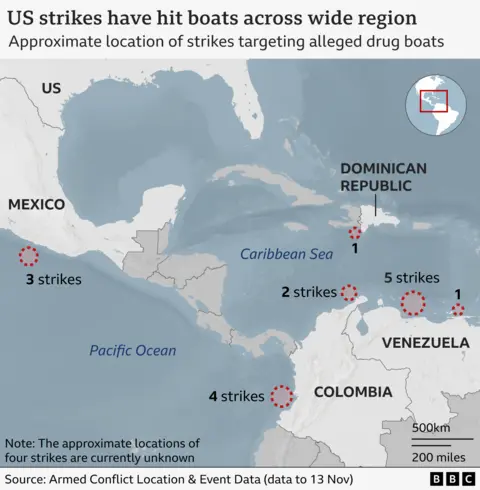

According to national rail operator Ukrzaliznytsia (UZ), there were twice as many attacks in September as there were in August - not just on trains but on the infrastructure that supports the rail network.

In fact, half of the attacks on the railways since the beginning of the war have taken place in the past two months, says Oleksiy Balesta, a deputy minister at the department that oversees the rail network.

Balesta suggests Russia has been hunting for locomotives - deliberately targeting both freight and passenger trains.

Behind the deputy minister is a wrecked locomotive, part of Ukraine's intercity fleet that was targeted in eastern Kyiv on one particularly devastating night at the end of August.

As he speaks, Balesta receives a message from his assistant. There has been another attack on a train between Kramatorsk and Sloviansk in the eastern Donetsk region, close to the front line.

Already today there have been three bomb threats on other services, forcing staff to evacuate the trains until explosives experts have given the all clear.

It’s a very clear battle for the railways, says Oleksandr Pertsovskyi, chief executive of UZ.

Repairing damage as fast as possible, coordinating with the military and training its staff to recognize potential sabotage threats are all key to Ukraine's response, says Pertsovskyi.

The goal is never to cancel a single service or destination. If a train can't run, we combine trains and buses.

This constant threat means flying people and supplies around the country is nearly impossible. Much of the grain and iron ore exports that Ukraine's economy depends on is moved by train to the southern Black Sea ports, and westward through Poland.

In a message echoed by many Ukrainian officials, he calls on the country's allies to supply stronger air defenses.

But we're not desperate. We're preparing mentally and practically. Ukrainians remain strong in spirit.

That spirit looks set to be tested to the limit in the coming months.