An impending crisis over conscripting ultra-Orthodox Jews into the Israeli army is threatening to undermine Israel's government and split the country.

Public opinion on the issue has shifted dramatically in Israel after two years of war, and this is now perhaps the most explosive political risk facing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Lawmakers are currently considering a draft bill to end the exemption granted to ultra-Orthodox men enrolled in full-time religious study, established when the State of Israel was declared in 1948.

That exemption was ruled illegal by Israel's High Court of Justice almost 20 years ago. Temporary arrangements to continue it were formally ended by the court last year, forcing the government to begin drafting the community.

Some 24,000 draft notices were issued last year, but only around 1,200 ultra-Orthodox - or Haredi - draftees reported for duty, according to military testimony given to lawmakers.

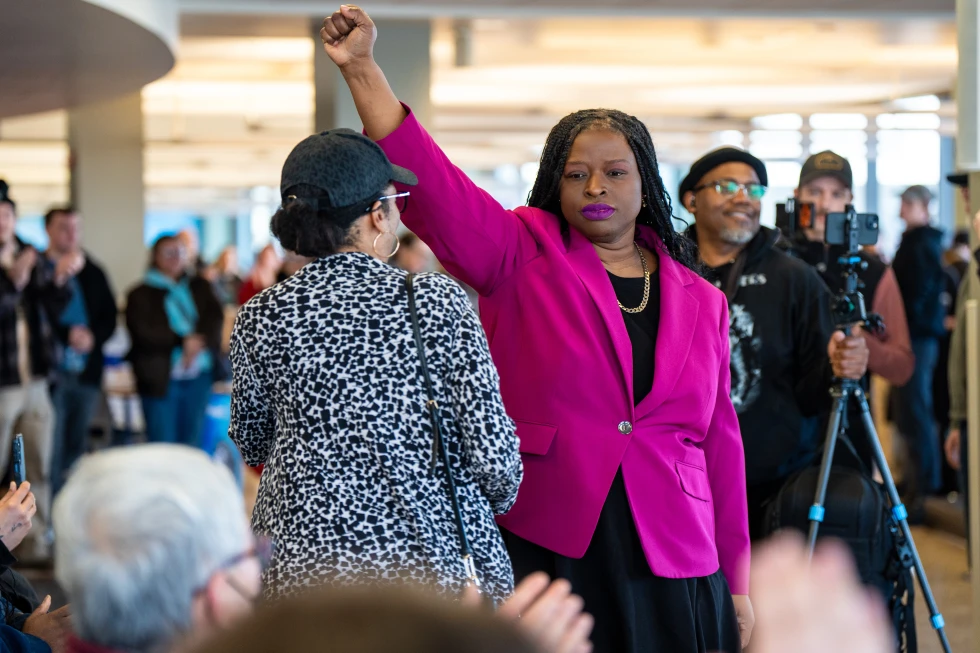

Tensions are erupting onto the streets, with lawmakers now debating a new draft bill to force ultra-Orthodox men into military service alongside other Israeli Jews.

Two Haredi politicians were targeted this month by some extreme ultra-Orthodox protesters, who are furious with parliament's discussion of the proposed law.

And last week, a special Border Police unit had to rescue Military Police officers who were targeted by a large crowd of Haredi men as they tried to arrest a suspected draft-evader.

These arrests have sparked the creation of a new messaging system called 'Black Alert' to spread word quickly through ultra-Orthodox communities and summon protesters to prevent arrests taking place.

The push to conscript more ultra-Orthodox also triggered a vast protest by tens of thousands of Haredi men in Jerusalem last month - with the issue seen by many as part of a wider conflict around the identity of the Jewish state, and the place of religion within it.

'We're a Jewish country,' said Shmuel Orbach, one of the protesters. 'You can't fight against Judaism in a Jewish country. It doesn't work.'

But the changes blowing through Israel have not yet breached the walls of the Kisse Rahamim yeshiva - or Jewish seminary - in Bnei Brak, an ultra-Orthodox city on the outskirts of Tel Aviv.

Inside the classroom, teenage boys sit in pairs to discuss Judaism's religious laws, their brightly coloured school notebooks popping against the rows of white shirts and small black kippahs (traditional skullcaps).

'Come at one in the morning, and you will see half the guys are studying Torah,' the head of the yeshiva, Rabbi Tzemach Mazuz, told me.

Ultra-Orthodox believe continuous prayer and religious study protect Israel's soldiers, and are as crucial to its military success as its tanks and air force. That belief was accepted by Israel's politicians in the past, Rabbi Mazuz said, but he acknowledged that Israel was changing.

Opinion polls suggest support for ultra-Orthodox conscription is rising. A survey in July by the Israel Democracy Institute think tank found that 85% of non-Haredi Jews supported sanctions for those who refused a draft order.

Support for extending the draft is also coming from religious Jews outside the Haredi community, like Dorit Barak, who lives near the yeshiva in Bnei Brak and points to non-Haredi religious Jews who do serve in the military while also studying Torah.

The draft bill now going through parliament is an attempt to find a way through the issue, or at least to buy time ahead of elections due next year. The current text, however, appears to largely maintain the status quo by conscripting only those ultra-Orthodox men not in full-time religious study, and lifting all sanctions on draft-dodgers once they turn 26.

As the nation grapples with this contentious topic, the political landscape is poised for further turmoil, revealing deep divisions over the role of religion and military service in Israeli society.