The Rise of Open Conversations About Sweat: From Taboo to Trend

BBC

BBCListen to Michelle read this article

Alan Carr's days on The Celebrity Traitors looked perilous from the start. Just 32 minutes into the first episode, after the comedian had been selected as a traitor, his body started to betray him.

Beads of sweat began forming on his forehead, making his face shiny. I thought I wanted to be a traitor but I have a sweating problem, he admitted to cameras. And I can't keep a secret.

Professor Gavin Thomas, a microbiologist at the University of York, was watching the episode. [Alan] does sweat a lot - and it looks like eccrine sweat, he says, referring to a common type of sweat, which comes from glands all over the body that can be activated by stress.

Yet it was Carr's willingness to talk about his sweatiness - and the excitement of viewers who were quick to analyse it on social media - that was most striking of all.

Alan Carr is not the first. All sorts of well-known people, from Hollywood actors and models to singers, have opened up about bodily functions in ever more brazen detail over the last decade. (Fellow Traitors contestant, the actress Celia Imrie, admitted in an episode this week: I just farted... It's the nerves, but I always own up.)

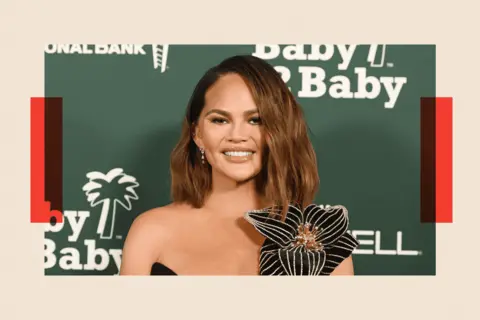

On sweat struggles specifically, Steve Carrell and Emma Stone have talked openly, and model Chrissy Teigen revealed in 2019 that the perspiration around her armpits was so irritating that she had Botox injections to prevent it. Then, singer Adele announced on stage in Las Vegas in 2023 that she had contracted a fungal infection as a result of perspiring.

I sweat a lot and it doesn't go anywhere, so I basically am just sitting in my own sweat, she told the thousands of people in the audience.

Now fitness shops sell sweat suits, for use during exercise - and then there is the very name of the longstanding British activewear brand Sweaty Betty. Its founder declared a few years ago: It's cool to sweat now.

So, does this all really signal the end of the once-widespread taboo about talking about perspiration?

At a sauna in Peckham, south London, young professionals sit on scorching hot, wood-panelled benches, dressed in swimming trunks and bathing suits. Outside, they dunk themselves in metal ice baths. A DJ plays music in the background.

Josh Clarricoats, 33, who owns a food start-up nearby, is a frequent visitor. He meets his business partner there every fortnight for meetings.

Actually our best creative thinking happens when we're there, he admits. It's something about sweating, being uncomfortable and the endorphins it releases.

Some professionals might have once felt awkward about sweating in front of colleagues, he concedes - but less so today. You get sweaty, you see your colleague dripping in sweat, I don't think people really worry about that.

Ultra-hot bathing houses have long been part of everyday life in Finland, where they are associated with löyly - the idea that sweat, heat, and steam help you reach a new spiritual state. But in recent years they've trickled into English-speaking countries.

There is a small but growing trend among British and American professionals, in particular, who are adopting the Finnish saunailta tradition, and meeting work colleagues inside saunas.

Last month The Wall Street Journal declared that the sauna has become the hottest place to network. The idea is that sweat puts everyone on the same level, lowering inhibitions and making it easier to forge relationships.

In Scandinavia, sauna diplomacy has long been used to lubricate high-level talks - in the 1960s, Finnish president Urho Kekkonen took the leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Krushchev, into an all-night sauna to persuade him to allow Finland to repair relations with the West.

Chains of high-end saunas are now springing up in San Francisco and New York too, with members paying as much as $200 (£173) per month to sweat together - in luxury.

There are now more than 400 saunas in the UK, according to the British Sauna Association, a sharp rise from just a few years ago. Gabrielle Reason, a physiologist and the association's director, has her own surprising view on why. When you're sweating [in a sauna] … you look an absolute mess but there's something actually very liberating about that, in a world that is very image-focused. You smell, you're bright red... You just stop caring what you look like.

It wasn't always this way. We've long had a complicated relationship with sweat - and for years, it was a source of fear. In medieval England, word spread about a supposed sweating sickness that was said to kill its victims within six hours. Some think that Mozart died after contracting the Picardy sweat, a mysterious illness that made victims drip with perspiration (though the composer's real cause of death remains unclear).

But this fear of sweat was turbocharged in English-speaking countries in the early 20th Century when hygiene brands realised they could use it to sell deodorants, according to Sarah Everts, a chemist and author of The Joy of Sweat.

She argues that marketing directed at young women highlighted the shame attached to perspiration. One advert for a deodorant called Mum published in an American magazine in 1938 urged women to face the truth about underarm perspiration odour.

Ms Everts illustrates this with a quote: Men do talk about girls behind their backs. Unpopularity often begins with the first hint of underarm odour. This is one fault men can't stand - one fault they can't forgive.

This shame is entrenched in Western culture, says Ms Everts, who has long suffered embarrassment about her own clammy skin. In a hot yoga class, I'd notice that the first drip of sweat would always come from me, she recalls. And I started to think, 'this is a space where I'm supposed to be sweating, and yet I'm mortified'.

But in recent years, that shame has started to fritter away - at least in some quarters.

The new mood is partially driven by the beauty industry and its revised message: embrace your perspiration. Back in 2020, Forbes described public sweatiness as the hottest and coolest fashion trend, and Vogue Magazine has run photo features on the charm of a sweaty face, known as post-gym skin.

Dove launched a marketing campaign in 2023 urging customers to post photographs of their sweaty armpits under the hashtag Free the Pits. Remi Bader, a TikTok beauty influencer enhancing body positivity, stated: I'm very, very open with my followers about how I'm very sweaty. It's so normal.

And what started as niche or a marketing ploy may well have filtered down to the rest of us. Zoe Nicols, a mobile beauty therapist and former salon owner in Dorset, says she's had customers asking for a sweaty makeup look. She describes it as a new Sweaty Hot Girl aesthetic ... you want to look like you've just done a hot yoga class or stepped out of the sauna.

However, Ms Everts holds a more sceptical view, stating that while it’s positive that people are speaking more openly about their bodies, the trend appears harnessed by the personal hygiene industry for commercial gain.

It's the next generation of these marketing strategies. Instead of being like, 'You smell - and that sucks', they say, 'you smell - but we all smell, here's a product that is the solution to that problem'.

Perspiration itself has basic benefits, primarily cooling us down. Dr Adil Sheraz, a dermatologist, points out that the most common form of sweat - eccrine sweat - regulates body temperature effectively. It comes from glands that number in the millions on our bodies and evaporates to lower temperature.

Ms Everts argues that sweating has roots in prehistoric developments, enabling early humans to work energetically under the sun. Fitness spas now promise to sweat out toxins, but scientific evidence supporting this idea remains limited. The mainstream skepticism questions the credibility of such claims.

“It's completely bananas,” says Ms Everts regarding the notion that meaningful toxins are expelled through sweating.

Hidden behind these discussions is a segment of the population for whom sweating is less about social norms and more of a medical issue. Hyperhidrosis qualifies as a medical condition characterized by excessive sweating without a clear cause, affecting an estimated 1-5% of people.

Melissa, who chose to remain anonymous, shares her experiences growing up with the condition: My hands and feet were constantly sweaty, even when it wasn't hot or nervous. I sometimes avoided physical contact because I worried people would notice or react badly.

Yet there's optimism due to a growing consciousness surrounding the condition. The societal interest in sweat seems poised to expand in the years to come, especially with climate change complicating our relationship with perspiration. Prof Filingeri believes we may see limits to how well we can sweat as temperatures rise, although air conditioning might alleviate some of these concerns.

In conclusion, as we confront increasing temperatures and changing societal values, perhaps it’s time to abandon the shame surrounding sweat and foster a more relaxed attitude to this natural bodily function, echoing the sentiment that embracing our imperfections is part of the collective journey towards body positivity.