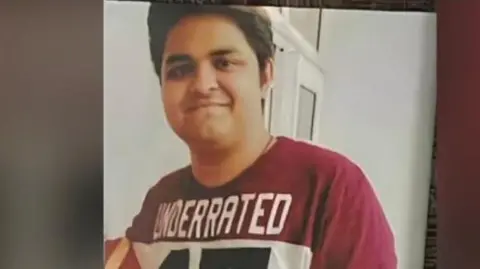

Bahison Ravindran always believed that he was Indian. Born to Sri Lankan refugee parents in Tamil Nadu, he grew up with a sense of belonging in the country he considered home. However, a shocking turn of events unveiled his precarious legal status.

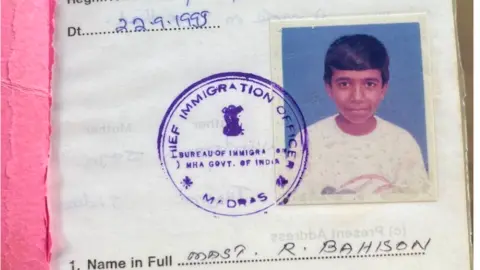

The 34-year-old web developer, who had studied and worked in India, was arrested in April after police identified his passport as invalid. Authorities claimed he was not an Indian citizen by birth because both his parents were Sri Lankans who migrated to India in 1990 during the civil war. According to Indian law, any child born after July 1, 1987 must have at least one parent who is an Indian citizen to qualify for citizenship.

Ravindran, born in 1991 shortly after his parents’ arrival, stated he was unaware of this specific requirement and had never concealed his ancestry. With the revelation that he was not considered a citizen, he promptly applied for naturalization, but now finds himself in the limbo of statelessness.

His predicament highlights a significant issue impacting over 22,000 individuals similarly born in India to Sri Lankan Tamil parents since the amendment. Many Sri Lankan Tamils fled to India during conflicts in their home country, and now they, along with Mr. Ravindran, face uncertain futures without recognized citizenship.

Adding to the complexity, dating back to the 1980s, the Indian government does not recognize Sri Lankan refugees as legitimate asylum seekers as it has neither signed the 1951 UN Refugee Convention nor the accompanying protocol.

The Citizenship Amendment Act of 2019 further complicates matters by excluding Tamils from Sri Lanka when providing expedited citizenship for persecuted non-Muslim minorities. Political discourse in Tamil Nadu often circles around aiding these refugees, yet tangible resolutions for citizenship remain elusive for many.

Only a handful of Sri Lankan Tamils have been granted citizenship since the law passed, with the first granted citizenship only in 2022. Now, Mr. Ravindran is hopeful his case will pave the way for recognition, having committed his life to India and feeling no intention to return to his ancestral land.

Despite only visiting Sri Lanka once for a short marriage trip, Mr. Ravindran’s legal troubles escalated after he applied for a new passport that included his wife's name. Following a brief arrest for multiple charges, he has since petitioned the Madras High Court, which has held off on any punitive measures while it examines his case.

“For these years, no one ever informed me that I was not Indian,” Mr. Ravindran expressed, grappling with his newly assigned label as a 'stateless person.' His journey underscores the ongoing struggle faced by refugees seeking recognition and belonging in a land they consider home.