Last Friday, at around 19:00, an Israeli air strike hit a car in a village in southern Lebanon called Froun. This part of the country is the heartland of the Shia Muslim community, and for decades has been under the sway of Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shia militia and political party. On streets, banners with the faces of fighters killed in battle hang from lamp-posts, celebrating them as martyrs of the resistance.

I arrived in Froun an hour after the strike. Rescue workers had already removed the body parts of the only casualty - a man who was later described as a Hezbollah terrorist by the Israeli military. Despite a ceasefire deal that came into force last November, ending the latest war with Hezbollah, Israel has continued with its bombing, almost every day.

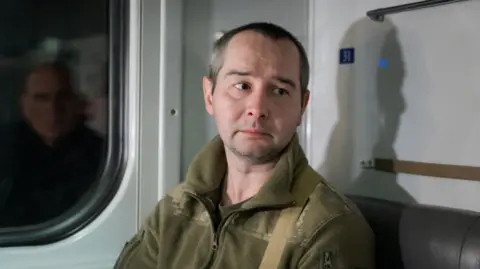

Who is going to help us? one resident, Mohamad Mokdad, asked me. The car had been hit as it passed in front of his house, and he was still cleaning up the veranda. There were body parts here and in the trees. He sounded despondent.

We're against all this... I just want to live in peace. I don't want parties, he said. He did not mention Hezbollah - which means Party of God - by name, but that is probably what he meant. I don't want anyone.

Israel says it is targeting Hezbollah and the group's efforts to recover after being severely weakened in the war. I travelled to southern Lebanon to see the impact of the Israeli campaign, and saw that the attacks had shattered people's sense of security and even some long-held views in areas where Hezbollah has traditionally enjoyed widespread support.

The ceasefire in Lebanon ended 13 months of war that killed 4,000 Lebanese and 120 Israelis. Israel and Hezbollah have been fighting for decades, and this conflict started when Hezbollah began firing rockets and missiles at Israeli positions a day after Israel launched its massive military response to the Hamas-led attacks on 7 October 2023.

The truce, brokered by the US and France, required Hezbollah to remove its fighters and weapons from the south of the Litani river, about 30km (20 miles) from the border with Israel, and Israeli troops to withdraw from areas of southern Lebanon that they invaded during the war. Thousands of Lebanese soldiers would then be sent to areas that had been effectively under Hezbollah control.

A year later, the Israeli military continues to occupy at least five hilltops in southern Lebanon and has carried out air and drone attacks across the country on targets it claims are linked to Hezbollah. Last Sunday, it killed the group's chief of staff and four others in a strike on a building in the Dahieh district, outside Beirut.

Unifil, the United Nations peacekeeping force in Lebanon that operates south of the Litani, says Israel has committed more than 10,000 air and ground violations during the ceasefire. According to the Lebanese health ministry, more than 330 people have been killed in Israeli attacks, including civilians.

Israeli officials say Hezbollah has been working to rebuild its military capabilities south of the Litani, which would be a violation of the ceasefire, and also tried to smuggle weapons into Lebanon while ramping up the production of explosive drones as an alternative to rockets and missiles.

So far, Israel has not made the evidence it says it has public. But, for weeks, Israeli journalists have been briefed on plans for a possible escalation against the group. Hezbollah is playing with fire, and the president of Lebanon is dragging his feet, Israel Katz, the Israeli defence minister, said recently.

Last week, Lt Col Avichay Adraee, the Arabic spokesman for the Israeli army, published on social media a warning for the Lebanese village of Beit Lif: Israel had detected dozens of terrorist infrastructures belonging to Hezbollah and would act to remove any threat. Worried that an attack could be imminent, residents made a public appeal for Lebanese soldiers to be deployed.

I visited Beit Lif the following morning. The village had a pre-war population of around 8,000; now, less than a third remains.

As we spoke, half a dozen men gathered around us on the grounds of a mosque that had been destroyed in an Israeli air strike during the war. Quietly, one of them told me: Hezbollah needs to decide: it either responds to Israel or accepts defeat, disarms and let us move on with our lives. This can't continue.

Public criticism of Hezbollah is still rare but, exhausted, some appear to be questioning the old consensus. We then heard a distant sound – from Israeli fighter jets in the sky.

A man called Haider, whose family owned a house that had been marked by the Israeli military as being used by Hezbollah, insisted on taking me to visit it. Outside, a poster remembered his brother, a Hezbollah fighter, who had been killed in the war. Haider said he wanted to prove there was nothing wrong there, appearing to believe that by being in the media he would, somehow, be protected. You can enter room by room and check with your own eyes, he said. It is difficult for us to confirm what could be happening here. He later said: We want stability, we don't want war, or anything related to it.

Despite the warning, Israel has not attacked the village.

A few metres away, I saw a man outside one of the few standing houses. Nayef al-Rida had moved there with his wife and an elderly relative. We could hear the constant sound of an Israeli drone, circling overhead. This happens 24/7, he said. I wondered how he felt living there. We've got every reason to be afraid, Mr Rida said. There's no-one here. You'll leave in a bit, and we'll be left alone.

In Yaroun's square, a billboard with a picture of the late Hezbollah leader, Hassan Nasrallah, killed in an Israeli air strike in the Dahieh when the conflict escalated last year, remained largely intact. In the meantime, Lebanese communities along the frontier are still in ruins. Tens of thousands of Lebanese remain displaced, without knowing when - or if - they will be able to return.

As Northeastern Lebanon continues to fall deeper into despair, the voices demanding peace resonate louder, yet the path to tranquility remains obscured by the shadows of a conflict that has spanned generations.