Deputies in the Italian parliament have voted unanimously to introduce the crime of femicide – the murder of a woman motivated by gender – as a distinct law to be punished with a life sentence.

In a symbolic move, the bill was approved on the day dedicated to the elimination of violence against women worldwide.

The idea of a law on femicide had been discussed in Italy before, but the murder of Giulia Cecchettin by her ex-boyfriend was a tragedy that shocked the country into action.

In late November 2023, the 22-year-old was stabbed to death by Filippo Turetta, who then wrapped her body in bags and dumped it by a lakeside.

The killing was headline news until he was caught, but it was the powerful response of Giulia's sister, Elena, that has endured.

The murderer was not a monster, she said, but the healthy son of a deeply patriarchal society. They were words that brought crowds out across Italy demanding change.

Two years on, MPs have voted for a law on femicide after a long and passionately debated session of parliament. It makes Italy one of very few places to categorize femicide as a distinct crime.

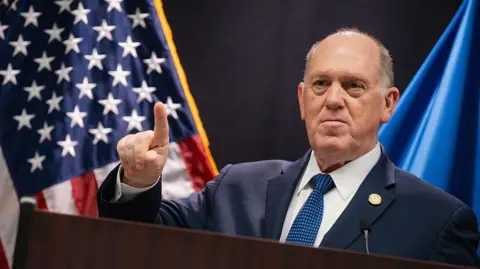

Introduced by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, the law was backed by her own hard-right government as well as opposition MPs. Many wore red ribbons or red jackets to remember the victims of violence.

From now on, Italy will record every murder of a woman that is motivated by her gender as femicide.

Femicides will be classified, they will be studied in their real context, they will exist, Judge Paola di Nicola, one of the authors of the new law, said of its significance.

She was part of an expert commission that examined 211 recent murders of women for common characteristics, then drafted the femicide law.

Italy will now join Cyprus, Malta, and Croatia as EU member states that have introduced a legal definition of femicide into their criminal codes.

The law will apply to murders which are an act of hatred, discrimination, domination, control, or subjugation of a woman as a woman, or that occur when she breaks off a relationship or to limit her individual freedoms.

The latest police data in Italy shows a slight fall in the number of women killed last year to 116, with 106 said to be motivated by gender. In future, such cases would be recorded separately and trigger an automatic life sentence, meant as a deterrent.

Gino Cecchettin isn't sure such a law would have saved his daughter: her killer was sent to prison for life in any case. But he does think defining and discussing the problem is important.

Before, many people especially from the centre and extreme right didn't want to hear the word femicide, Mr. Cecchettin told the BBC. Now this is a world where we can speak about it. That's a little step, but it's a step.

His own focus is on education, not legislation. After Giulia's murder, her father describes taking a very intense look into what was happening around me then deciding to create a foundation in her name devoted to preventing others suffering as his family has.

Italy's problems on that front are currently on display at the Museum of the Patriarchy, a thought-provoking new exhibition in Rome. Italy currently ranks 85th in the Global Gender Gap Index, almost the lowest of all EU states.

The femicide law itself has its critics. Law professor Valeria Torre believes the new definition of femicide is too vague and will prove difficult for judges to implement.

Even those who approve of legislating against femicide agree that it must come with far broader measures against gender inequality.