Last week, India announced it would implement what many say are its most far-reaching economic reforms in decades - compressing 29 federal laws that regulated labour into four simplified codes.

As a result, the number of rules that govern labour have now come down from a staggering 1,400 to around 350, while the number of forms companies had to fill in this regard have reduced from 180 to 73 - drastically lightening the regulatory burden on businesses.

The laws got a parliamentary nod in 2020 but are finally set to be uniformly implemented across the country after a five-year delay and much political wrangling.

Companies - which have long blamed restrictive labour practices for the atrophy in India's manufacturing sector - have given the changes a rousing welcome.

This is part of a broader trend by the government to hasten economic reforms, especially in the wake of Trump's 50% tariffs, and an important signal that it is keen to ease doing business in India, attract more FDI [foreign direct investment] and integrate into GVCs [global value chains], said Nomura, a broking house.

But trade unions are asking for their withdrawal and calling the codes the most sweeping and aggressive abrogation of workers' hard-won rights and entitlements since [India's] independence.

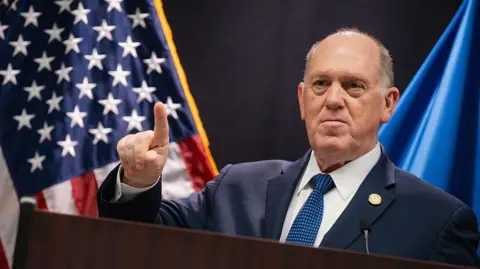

The changes have triggered demonstrations across the country, with 200-300 people turning up at a protest in capital Delhi on Wednesday, led largely by left-leaning trade unions not aligned with Prime Minister Narendra Modi's ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

At the protest site, Akashdeep Singh, a 33-year-old factory worker employed at an international beverage company on the outskirts of Delhi, told the BBC that the laws will benefit only the employers and not workers like us.

Several others expressed similar anxieties. The government says the long-pending reforms aim to modernise outdated laws, simplify compliance, and protect workers' rights - while giving legal recognition to India's growing gig workforce for the first time.

Several worker-friendly measures - mandatory appointment letters, uniform minimum wages, free annual health check-ups for those over 40, and gender-neutral pay - are welcome steps.

Coupled with fewer compliance burdens, stronger social security, and an expanded definition of employees to include gig workers, these reforms could help formalise India's vast informal economy, experts say.

The new codes also iron out glaring inconsistencies, such as varied definitions of the same rules that were prevalent in the previous laws, according to Arvind Panagariya, economist at Columbia University and former chairman of the Indian government's think tank Niti Aayog.

But even with the many welcome provisions, two contentious clauses in the reforms have particularly irked unions.

These include rules that will make it easier for companies to fire workers and also harder for workers to legally conduct strikes.

Earlier, factories with 100 or more workers needed the government's permission before they could lay off employees. Now, that threshold has been increased to 300.

Economists argue that the old rules barring layoffs in firms with 100 or more workers were draconian, hampering India's competitiveness compared to countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and China.

While ideological differences remain, experts broadly agree that the outdated and complex codes - often used by inspectors to harass factory owners - needed simplification.