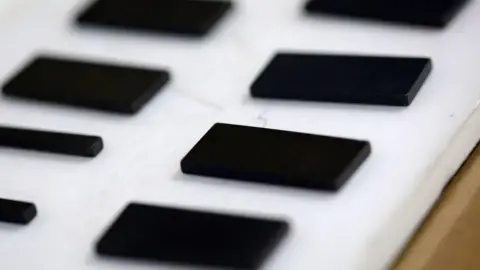

In November 2025, India approved a ₹73 billion ($800 million; £600 million) plan that aims to lessen its dependence on China for rare earth magnets, a crucial component in modern technology. These small yet powerful magnets are integral to a variety of applications, ranging from electric vehicles and wind turbines to smartphones and medical devices.

The government’s strategy centers on magnets, one of the most widely utilized rare-earth products, to expedite the development of a self-reliant ecosystem. However, a successful transition hinges on India's ability to acquire the necessary technology, secure raw materials, and scale production efficiently.

The initiative intends for selected manufacturers to receive incentives to produce 6,000 tonnes of permanent magnets annually within seven years, addressing a projected doubling of domestic demand in the next five years. Yet many industry experts caution that financial investment alone may not suffice.

Currently, India imports around 80-90% of its magnets and related materials from China, which oversees over 90% of the global rare earth processing market. In 2025, India imported approximately $221 million worth of these components, highlighting the country’s vulnerability, especially during instances when China restricts exports, as witnessed in a recent trade conflict that affected the automotive and electronics sectors.

While India is taking steps to strengthen its domestic supply chain through initiatives like the National Critical Mineral Mission, the path to self-sufficiency is challenging. The country has ample rare earth reserves, notably in coastal states, yet it struggles with operational mining capacity and expertise in magnet production, an area much advanced in countries like Japan and Germany.

Experts like Neha Mukherjee from Benchmark Mineral Intelligence emphasize that India needs to forge strategic partnerships for technology transfer and workforce development. Moreover, the supply of critical heavier rare earth elements needed for high-performance magnets—such as dysprosium and terbium—remains a significant concern, as current reserves mostly include lighter elements like neodymium.

In terms of production capacity, with India’s annual consumption of approximately 7,000 tonnes of magnets, even reaching the government's target of 6,000 tonnes by the early 2030s could leave the country at a disadvantage, particularly if demand spikes beyond projections.

Additionally, there’s a pressing challenge in ensuring that domestically produced magnets can compete with cheaper imports from China without undercutting their own market. Stakeholders advocate for not only incentives for manufacturers but also for buyers to foster local industry growth.

Despite the myriad of challenges ahead, analysts recognize the initiative as a significant step towards building a resilient domestic ecosystem for rare earth magnets, underscoring the importance of India’s ambitions in a competitive global landscape.