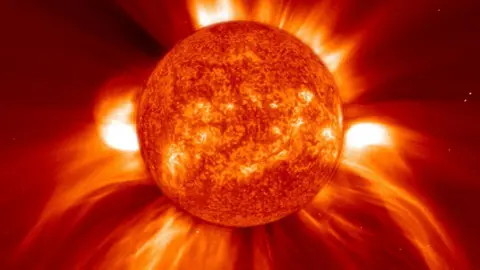

For Aditya-L1, India's first solar observation mission in space, the year 2026 is expected to be like no other. It's the first time the observatory, placed in orbit last year, will monitor the Sun during its maximum activity cycle. This phenomenon occurs approximately every 11 years when the Sun's magnetic poles flip, resulting in a turbulent period filled with increased solar storms and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). These massive explosions can release charged particles that weigh up to a trillion kilograms and travel at speeds of up to 3,000 km (1,864 miles) per second.

Prof R. Ramesh from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics emphasizes that during this peak phase, the Sun is expected to produce 10 or more CMEs daily, significantly up from the usual two to three during low-activity times. Monitoring these eruptions is crucial not only for scientific understanding but also for protecting Earth's infrastructure from potential disruptions caused by solar activity.

CMEs can cause geomagnetic storms that impact satellite functionality and electricity grids on Earth. The observable beauty of CMEs, such as auroras, contrasts sharply with their potential to disrupt technology and infrastructure. Historical events demonstrate the dangers: the Carrington Event of 1859 caused widespread telegraph failures, while more recent solar storms have caused power outages affecting millions.

Aditya-L1's unique coronagraph allows for continuous observation of the solar corona, akin to how the Moon blocks the Sun's bright surface during an eclipse. This capability will likely yield valuable data during the upcoming solar maximum. Collaborative studies with NASA are already underway to gauge the impact of significant CMEs recorded by Aditya-L1, setting a benchmark for understanding future solar activity.

With substantial mass and energy content, the CMEs anticipated during peak activity could rival catastrophic events in history. Prof Ramesh notes that understanding these solar phenomena also aids in establishing safeguards for satellite operations.

2026 is poised to be a transformative year for solar research and its practical implications, as India's Aditya-L1 mission evolves into a critical watchtower for solar dynamics.

Prof R. Ramesh from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics emphasizes that during this peak phase, the Sun is expected to produce 10 or more CMEs daily, significantly up from the usual two to three during low-activity times. Monitoring these eruptions is crucial not only for scientific understanding but also for protecting Earth's infrastructure from potential disruptions caused by solar activity.

CMEs can cause geomagnetic storms that impact satellite functionality and electricity grids on Earth. The observable beauty of CMEs, such as auroras, contrasts sharply with their potential to disrupt technology and infrastructure. Historical events demonstrate the dangers: the Carrington Event of 1859 caused widespread telegraph failures, while more recent solar storms have caused power outages affecting millions.

Aditya-L1's unique coronagraph allows for continuous observation of the solar corona, akin to how the Moon blocks the Sun's bright surface during an eclipse. This capability will likely yield valuable data during the upcoming solar maximum. Collaborative studies with NASA are already underway to gauge the impact of significant CMEs recorded by Aditya-L1, setting a benchmark for understanding future solar activity.

With substantial mass and energy content, the CMEs anticipated during peak activity could rival catastrophic events in history. Prof Ramesh notes that understanding these solar phenomena also aids in establishing safeguards for satellite operations.

2026 is poised to be a transformative year for solar research and its practical implications, as India's Aditya-L1 mission evolves into a critical watchtower for solar dynamics.