The Black Hawk helicopter was ready for take off – its rotor blades slicing through the air in the deadening heat of the Colombian Amazon. We ducked low and crammed in alongside the Jungle Commandos – a police special operations unit armed by the Americans and originally trained by Britain's SAS, when it was founded in 1989.

The commandos were heavily armed. The mission was familiar. The weather was clear. But there was tension on board, kicking in with the adrenaline. When you go after any part of the drug trade in Colombia, you have to be ready for trouble.

The commandos often face resistance from criminal groups, and current and former guerrillas who have replaced the cartels of the 1970s and 80s.

We took off, flying over the district of Putumayo - close to the border with Ecuador - part of Colombia's cocaine heartland. The country provides about 70% of the world's supply.

Just ahead two other Black Hawks were leading the way.

Down below us there was dense forest and patches of bright green – the tell-tale sign of coca plant cultivation. The crop now covers an area nearly twice the size of Greater London, and four times the size of New York, according to the latest figures from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), published in 2024.

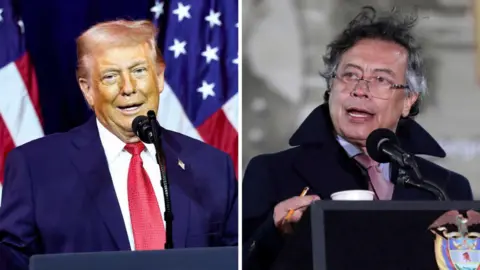

President Donald Trump says Colombia's left-wing President Gustavo Petro is not doing enough to prevent cocaine from his country winding up on America's streets. Last month he called him a 'sick man who likes selling cocaine to the United States' and said 'he could be next' for US military intervention. But that threat appears to have receded.

The fight against drug production and trafficking from Colombia will be high on the agenda when the two presidents meet in the White House on Tuesday.

After 20 minutes, we land at a clearing in the jungle and see the first stage of a global drug trade. The commandos lead us to a crude cocaine lab, partly hidden by banana trees. It's little more than a shack but it has the key ingredients – drums of chemicals and a mound of fresh coca leaves, ready to be turned into a paste.

Minutes later we are rushed away as the commandos prepare to set the lab alight – destroying the crop, and the chemicals. There are 50 or 60 more labs in this area, says one officer, who does not want to be named.

Dense black smoke rises from the forest as we take off. An energy drink is handed around among the commandos, who could soon be doing this all over again. Weather permitting, it's rinse and repeat. They carry out these operations several times a day.

Back at base, Major Cristhian Cedano Díaz takes a few moments to unwind with his men. He's a 16-year veteran of the war on drugs, standing ram rod straight, with a handgun in a holster around his neck - and with no illusions. When asked how quickly a drug lab can be rebuilt, his response is immediate. 'In one day,' he says, with a rueful smile. 'It's just a matter of changing or moving a few metres. We have seen it before. Sometimes, when we return to areas where operations have taken place, we find structures have been rebuilt just a few metres away.'

But he insists that destroying one lab after another serves a purpose. 'We are affecting the profitability of the criminal groups,' he says. 'They can rebuild countless times, but they are losing the coca crop, and the chemical precursors they need.'

His enemy is evolving. Colombia's drug gangs use drones and bitcoin and bring chemists into the jungle to create ingredients on site. Major Cedano Díaz, 37, admits the cocaine war may not be over his lifetime.

But both Major and the farmer, who is caught in a cycle of despair who we come to call 'Javier', have one hope in common—the dream for their children to inherit a different Colombia.

As Javier states, "If you want to survive, you have to" grow coca, lamenting the lack of economic opportunities that drive him back to a dangerous trade, asking for understanding rather than threats from international powers. Each man stands on opposite sides of a conflict that retains its tragic complexity.