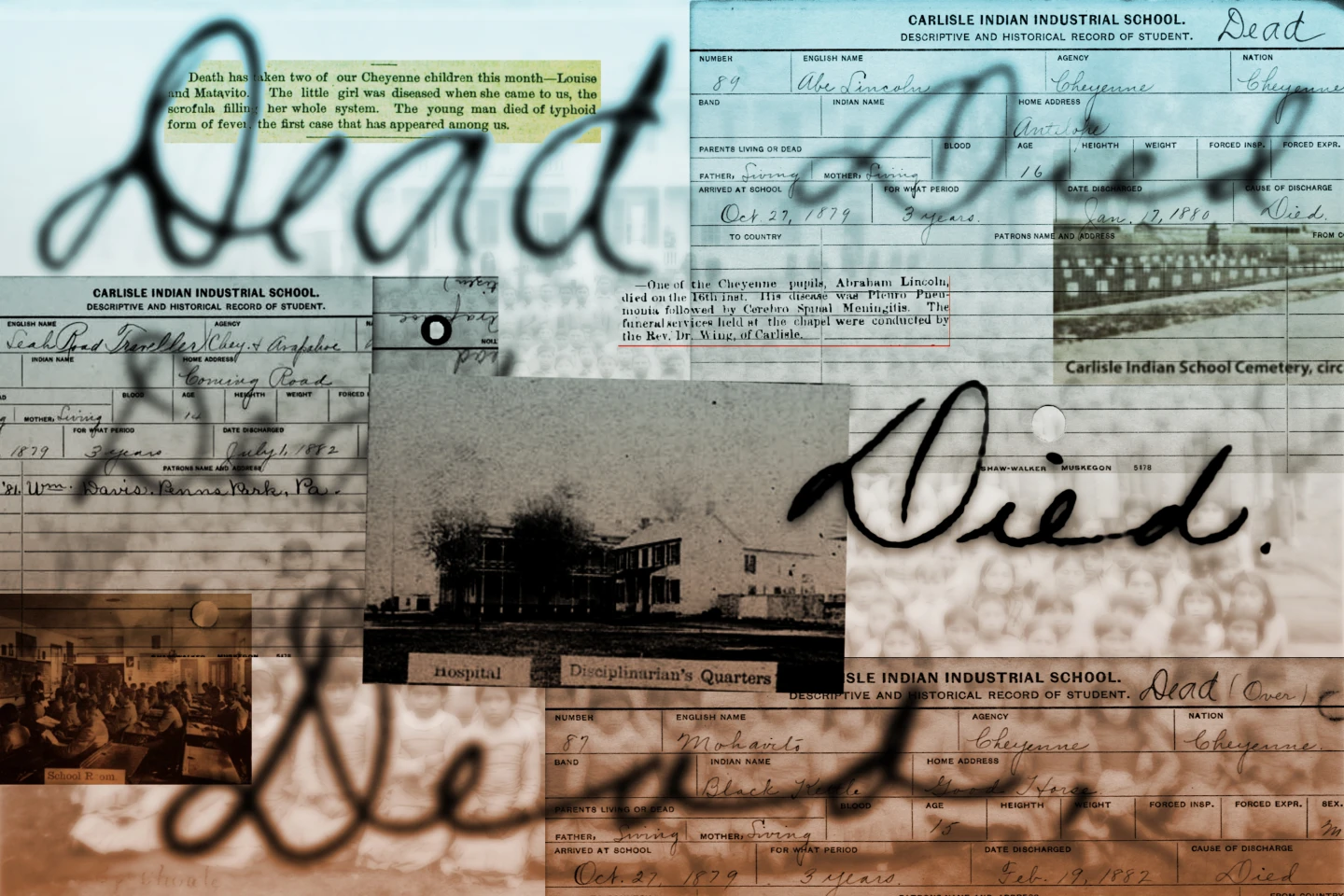

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School had not yet held its first class when Matavito Horse and Leah Road Traveler were taken there in October 1879, drafted into the U.S. government’s campaign to erase Native American tribes by wiping their children’s identities.

A few years later, Matavito, a Cheyenne boy, and Leah, an Arapaho girl, were dead.

Persistent efforts by their tribes have finally brought them home. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma received 16 of its children, exhumed from a Pennsylvania cemetery, and reburied their small wooden coffins last month in a tribal cemetery in Concho, Oklahoma. A 17th student, Wallace Perryman, was repatriated to the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma in Wewoka.

Burial ceremonies are “an important step toward justice and healing for the families and Tribal Nations impacted by the boarding school era,” the Cheyenne and Arapaho government said. Some details are lost to history, but records in the National Archives shed light on the experiences at Carlisle, where 7,800 students from more than 100 tribes were sent amid genocidal warfare.

The tribally acknowledged children were involved in various activities, from tending fires and raising pigs to mastering sewing skills. Some even endured baptism.

Who were the children?

Health records reveal the grim realities many faced, with some dying from tuberculosis and typhoid fever. These efforts reflect broader movements among Native tribes to restore dignity and honor to their ancestors amid a history fraught with trauma and cultural erasure.

Despite ongoing battles for repatriation and accountability, the return of these 17 children symbolizes a significant reclaiming of identity and history for Native American tribes.

Having faced severe hardships, these tribes are now taking proactive measures to recover the histories and identities of their lost children from a painful past.