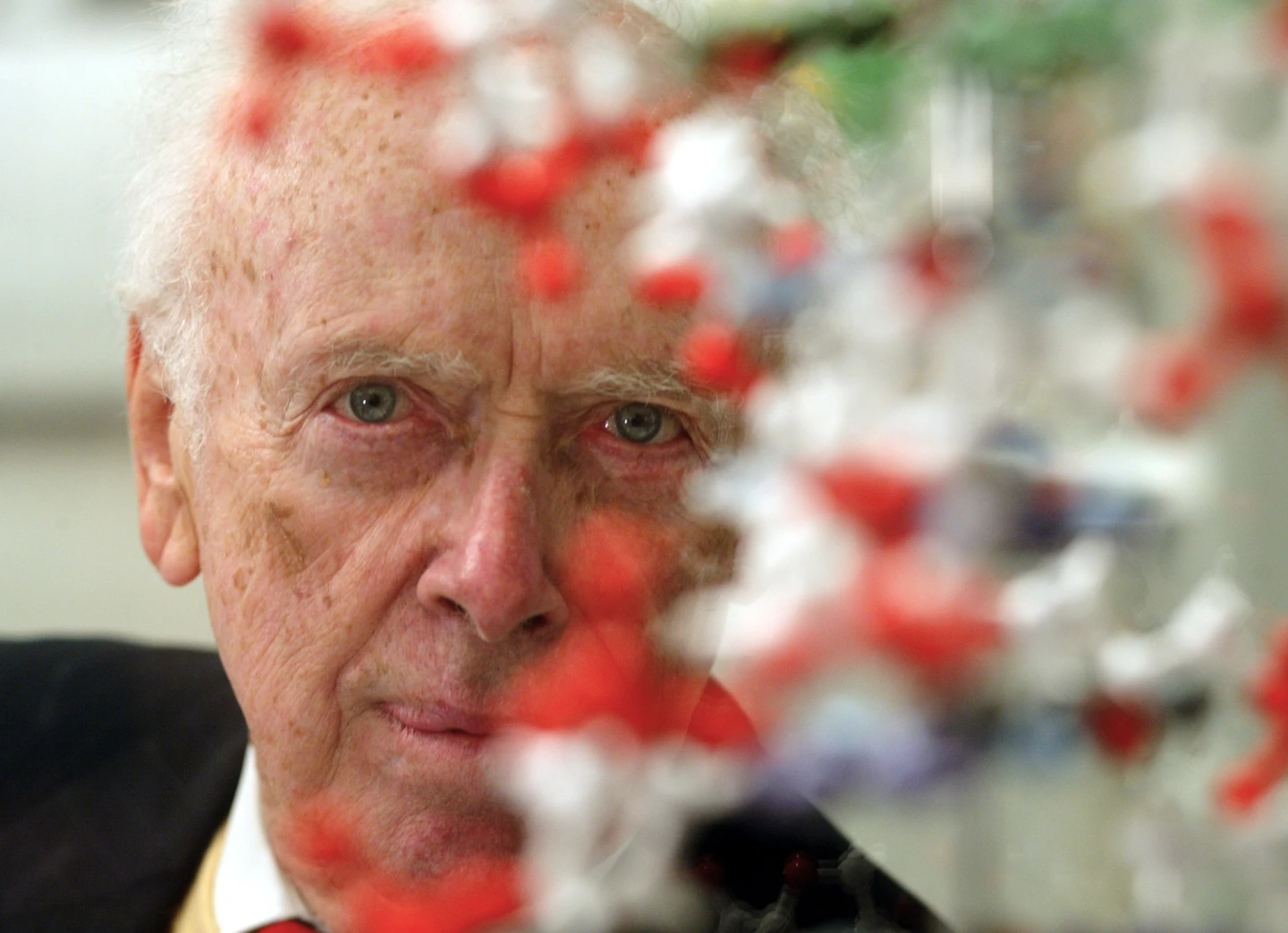

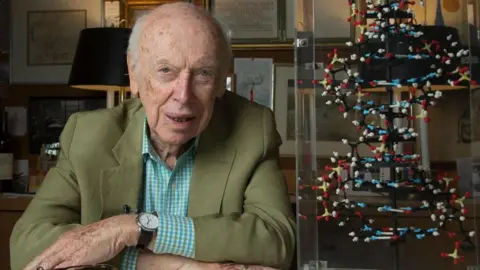

James D. Watson, whose co-discovery of the twisted-ladder structure of DNA in 1953 helped light the long fuse on a revolution in medicine, crimefighting, genealogy, and ethics, has died. He was 97.

The breakthrough—made when the brash, Chicago-born Watson was just 24—turned him into a hallowed figure in the world of science for decades. However, near the end of his life, he faced condemnation and professional censure for offensive remarks, including saying Black people are less intelligent than white people.

Watson shared a 1962 Nobel Prize with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for discovering that deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is a double helix, consisting of two strands that coil around each other resembling a long, gently twisting ladder.

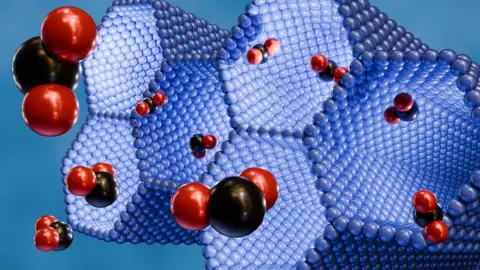

This realization suggested how hereditary information is stored and how cells duplicate their DNA. The duplication begins with the two strands of DNA pulling apart like a zipper.

Even among non-scientists, the double helix became an instantly recognized symbol of science, appearing in various cultural contexts, including art and postage stamps.

The discovery paved the way for more recent developments such as tinkering with the genetic makeup of living things, treating diseases, and tracing family trees, while also raising ethical questions regarding genetic manipulation.

Watson stated, 'Francis Crick and I made the discovery of the century, that was pretty clear.' He later noted, 'There was no way we could have foreseen the explosive impact of the double helix on science and society.'

While Watson found immense success, he also drew criticism for creating a complicated legacy, particularly due to comments he made regarding race, which overshadowed his scientific achievements. In 2007, he faced significant backlash for declaring he was 'inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa' and attributing disparities in intelligence to race.

Watson passed away in hospice care after a brief illness, with his son noting that he 'never stopped fighting for people who were suffering from disease.'

Born on April 6, 1928, Watson had shown a keen interest in genetics from a young age. Despite his significant contributions, his remarks and views led to a tarnished professional reputation, culminating in the revocation of honorary titles by fellow researchers who deemed his opinions 'reprehensible'.

Watson's legacy as a groundbreaker in genetic research is woven with the cautionary tale of a scientist whose views on race and intelligence drew ire and controversy that remain profound in discussions of ethics in science today.