Han Tae-soon, now 71, has finally reunited with her long-lost daughter, Kyung-ha, after 44 years apart – but their relationship is marred by illegal adoption practices and a struggle for redress. The Japanese-born Kyung-ha, later known as Laurie Bender in the US, was abducted as a child and adopted without her mother's consent. Han is suing the South Korean government for failing to prevent illegal adoptions, part of a troubling history where thousands of children were sent abroad under suspicious circumstances as part of a state-sanctioned program that persisted from the 1950s onward. This case highlights the devastating effects of South Korea’s adoption policies, as Han's search for her daughter exemplifies the pain experienced by many parents and adoptees caught in this system.

"Reunited After Decades: A Mother’s Legal Battle Against South Korea’s Adoption Practices"

"Reunited After Decades: A Mother’s Legal Battle Against South Korea’s Adoption Practices"

A heartfelt reunion unveils a mother's anguish sparked by her daughter's illegal adoption decades earlier, leading to a landmark lawsuit against South Korea's government.

The details of their reunion are painful but filled with the hope of healing. Han's journey bore years of agony, fruitless searches, and failed leads until a DNA match revealed her daughter's whereabouts nearly five decades later. Their reunion showcased both the joy of reconnection and the sorrow of lost time, leading to Han's call for accountability from a government that, she claims, facilitated such practices. With her landmark case set to go to court next month, Han’s pursuit of justice may signal a broader reckoning for South Korea's adoption policies, amid growing recognition of systemic failures and a collective demand for reparation.

As South Korea begins to grapple with its adoption history, the public's appetite for reform grows alongside a desperate need for the government to acknowledge its complicity in these violations of human rights.

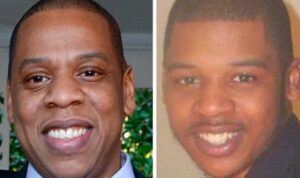

Han Tae-soon had spent decades looking for her daughter Kyung-ha. The last memory Han has of her daughter as a child is from May 1975, at their home in Seoul. "I was going to the market and asked Kyung-ha, 'Aren't you coming?' But she told me, 'No, I'm going to play with my friends'," recalled Ms Han. "When I came back, she was gone." Ms Han would not see her daughter again for more than four decades. When they reunited, Kyung-ha was almost unrecognizable as a middle-aged American woman named Laurie Bender.

Kyung-ha had been kidnapped near her home, allegedly taken to an orphanage, and then sent illegally to the US to be raised by another family, according to Ms Han, who is now suing the South Korean government for failing to prevent her daughter's adoption. She is among hundreds of individuals who have come forward in recent years with accusations of fraud, illegal adoptions, and human trafficking in South Korea’s controversial overseas adoption program. Since its inception in the 1950s, South Korea has sent roughly 170,000 to 200,000 children abroad for adoption, making it the world leader in this regard.

A recent landmark inquiry uncovered that past governments had committed human rights violations through inadequate oversight, enabling private agencies to "mass export" children for profit. Experts predict the findings could inspire further lawsuits against the government. Ms Han's case is set for trial next month and marks a critical point in the quest for accountability.

With the support of a group called 325 Kamra, which connects overseas adoptees with their birth parents through DNA matching, Han's breakthrough in 2019 finally led her to her daughter, Laurie Bender. Their emotional reunion at Seoul's airport brought tears, as Han felt the need to touch Laurie's hair to confirm her identity. Despite their long separation, both women have expressed the profound relief and healing that comes with reconnection.

However, their relationship remains strained by distance and language barriers, with Kyung-ha having forgotten much of her Korean and Han diligently practicing her English every day. "Even though I have found my daughter, it doesn't feel like I've truly found her," Han expressed regretfully.

As South Korea contemplates and attempts to rectify its dark past regarding adoptions, the ongoing efforts of people like Han, coupled with potential legal precedents, may lead to fundamental changes in the governance of adoption practices and foster a future of greater accountability and more humane treatment of children.

As South Korea begins to grapple with its adoption history, the public's appetite for reform grows alongside a desperate need for the government to acknowledge its complicity in these violations of human rights.

Han Tae-soon had spent decades looking for her daughter Kyung-ha. The last memory Han has of her daughter as a child is from May 1975, at their home in Seoul. "I was going to the market and asked Kyung-ha, 'Aren't you coming?' But she told me, 'No, I'm going to play with my friends'," recalled Ms Han. "When I came back, she was gone." Ms Han would not see her daughter again for more than four decades. When they reunited, Kyung-ha was almost unrecognizable as a middle-aged American woman named Laurie Bender.

Kyung-ha had been kidnapped near her home, allegedly taken to an orphanage, and then sent illegally to the US to be raised by another family, according to Ms Han, who is now suing the South Korean government for failing to prevent her daughter's adoption. She is among hundreds of individuals who have come forward in recent years with accusations of fraud, illegal adoptions, and human trafficking in South Korea’s controversial overseas adoption program. Since its inception in the 1950s, South Korea has sent roughly 170,000 to 200,000 children abroad for adoption, making it the world leader in this regard.

A recent landmark inquiry uncovered that past governments had committed human rights violations through inadequate oversight, enabling private agencies to "mass export" children for profit. Experts predict the findings could inspire further lawsuits against the government. Ms Han's case is set for trial next month and marks a critical point in the quest for accountability.

With the support of a group called 325 Kamra, which connects overseas adoptees with their birth parents through DNA matching, Han's breakthrough in 2019 finally led her to her daughter, Laurie Bender. Their emotional reunion at Seoul's airport brought tears, as Han felt the need to touch Laurie's hair to confirm her identity. Despite their long separation, both women have expressed the profound relief and healing that comes with reconnection.

However, their relationship remains strained by distance and language barriers, with Kyung-ha having forgotten much of her Korean and Han diligently practicing her English every day. "Even though I have found my daughter, it doesn't feel like I've truly found her," Han expressed regretfully.

As South Korea contemplates and attempts to rectify its dark past regarding adoptions, the ongoing efforts of people like Han, coupled with potential legal precedents, may lead to fundamental changes in the governance of adoption practices and foster a future of greater accountability and more humane treatment of children.