The timing of the first of several recent anti-gentrification protests in Mexico City was no coincidence - 4 July, US Independence Day.

Demonstrators gathered in Parque México in Condesa district – the epicentre of gentrification in the Mexican capital – to protest over a range of grievances. Most were angry at exorbitant rent hikes, unregulated holiday lettings, and the endless influx of Americans and Europeans into the city's trendy neighbourhoods like Condesa, Roma and La Juárez, forcing out long-term residents.

In Condesa alone, estimates suggest that as many as one in five homes is now a short-term let or a tourist dwelling. Others also cited more prosaic changes, like restaurant menus in English, or milder hot sauces at the taco stands to cater for sensitive foreign palates.

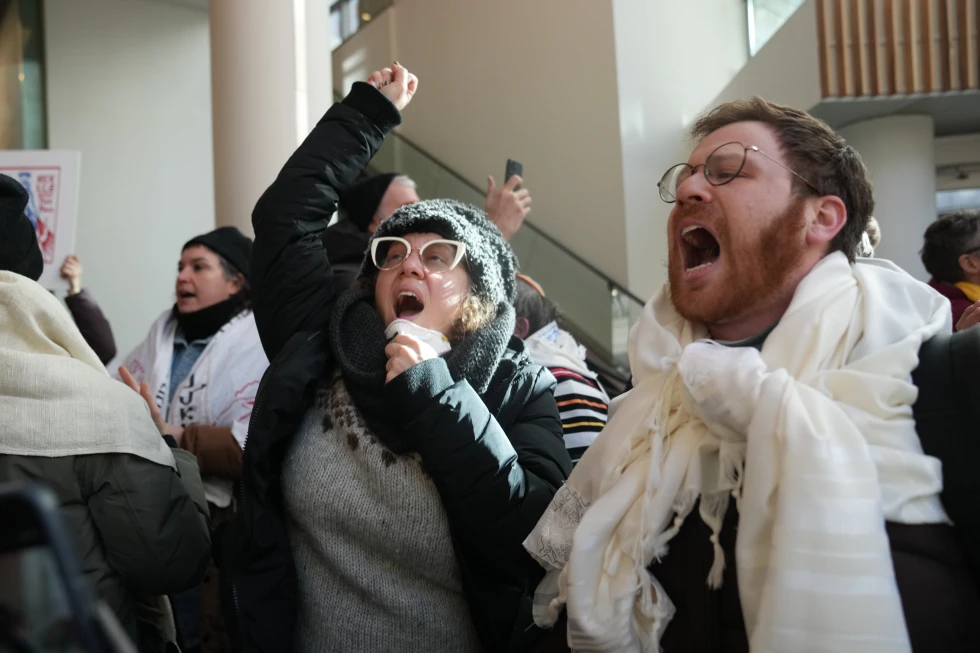

But as it moved through the gentrified streets, the initially peaceful protest turned ugly. Radical demonstrators attacked coffee shops and boutique stores aimed at tourists, smashing windows, intimidating customers, spraying graffiti and chanting Fuera Gringo!, meaning Gringos Out!.

At her next daily press conference, President Claudia Sheinbaum condemned the violence as xenophobic. No matter how legitimate the cause, as is the case with gentrification, the demand cannot be to simply say 'Get out!' to people of other nationalities inside our country, she said.

Masked radicals and agitators aside though, the motivation for most people who turned out on 4 July was stories like Erika Aguilar's. After more than 45 years of her family renting the same Mexico City apartment, the beginning of the end came with a knock at the door in 2017.

Long-term residents of the Prim Building, a 1920s architectural gem located in La Juárez district, they were visited by officials clutching eviction papers. Erika, the eldest daughter, recalls the shocking news: They came to every apartment in the building and told us we had until the end of the month to vacate the premises, as they weren't going to renew our rental contracts.

Today, her old home is covered by tarpaulin and scaffolding, as a construction team converts it into luxury apartments designed for short and medium-term rentals. It's not a construction for people like me, Erika comments ruefully.

Erika and her family now live far from the city centre, almost two hours away by public transport. This situation reflects a broader trend highlighted by activists, who have documented thousands of cases of forced displacement over the past decade. Sergio González, one of the protesters, referred to the crisis as an ongoing urban war over housing rights.

Despite the government's 14-point plan intended to address rising rents and protect residents, critics argue the measures are insufficient against the backdrop of systemic economic issues driven by neoliberal policies.

We have a local and federal government which continues to promote a neoliberal economic model, Sergio argues, insisting on the need for deeper change to tackle the root causes of gentrification.

While some newcomers are seen as contributing to the problem, others like Erika do not blame them but instead emphasize the need for responsible integration into the community. As Mexico City continues to evolve, the struggle against gentrification reveals the intense battle over identity, culture, and communal integrity in one of the world's most dynamic urban landscapes.