The UN climate summit COP30 in Belém, Brazil, concluded amidst significant tension and disappointment as it failed to secure new commitments for reducing fossil fuel usage. Despite collective efforts from over 80 countries, including major economies like the UK and EU, the final agreement did not directly address the urgent need to phase out oil, coal, and gas.

Countries heavily reliant on fossil fuels, particularly oil-producing nations, resisted calls for stricter regulations, arguing for their right to utilize these resources to support economic growth. This impasse worsens the global efforts needed to meet the critical temperature rise target of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, as expressed by the UN.

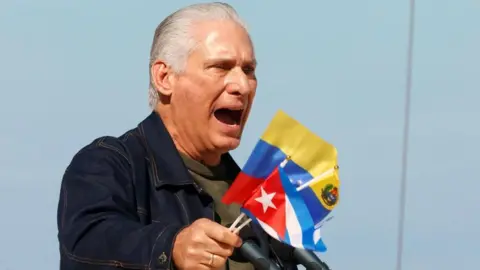

President Gustavo Petro of Colombia vehemently criticized the handling of the negotiations, lamenting that his country was not allowed to voice objections during the final plenary session. He publicly rejected the agreement, reflecting widespread sentiment among those advocating for a stronger stance against fossil fuel dependency.

The final document, named Mutirão, merely urges countries to voluntarily enhance their climate actions—a vague proposal that many regarded as insufficient. There were isolated moments of relief; some countries noted that the talks did not entirely collapse or regress on previous agreements. However, the absence of more assertive commitments left many negotiators unsettled.

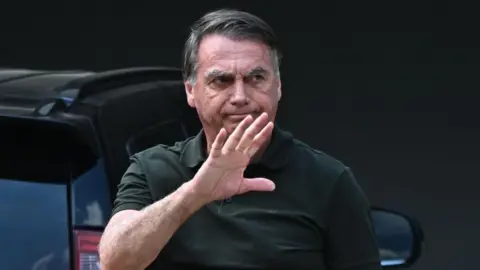

Compounding the proceedings was a chaotic environment plagued by logistical challenges. Delegates faced flooded venues, malfunctioning facilities, and significant disruptions, including a fire incident that necessitated evacuations. In a symbolic move, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva aimed to spotlight the Amazon rainforest during this summit, while simultaneously pursuing controversial offshore drilling plans that contradicted the climate dialogue.

On the flip side, some nations viewed the result as a step forward. Representatives from India described the deal as meaningful, while those representing small island states acknowledged its imperfections but considered it a progression. Nonetheless, many leaders, including Ed Miliband from the UK, expressed dissatisfaction over the lack of ambition and specific financial commitments for developing countries struggling to tackle climate impacts.