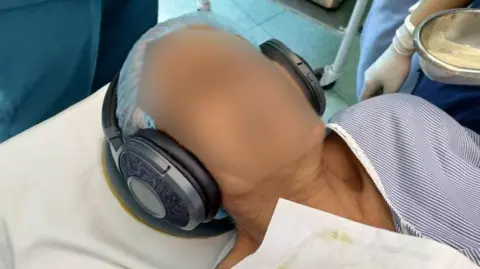

Under the harsh lights of an operating theatre in the Indian capital, Delhi, a woman lies motionless as surgeons prepare to remove her gallbladder. She is under general anaesthesia: unconscious, insensate and rendered completely still by a blend of drugs that induce deep sleep, block memory, blunt pain and temporarily paralyse her muscles. Yet, amid the hum of monitors and the steady rhythm of the surgical team, a gentle stream of flute music plays through the headphones placed over her ears.

Even as the drugs silence much of her brain, its auditory pathway remains partly active. When she wakes up, she will regain consciousness more quickly and clearly because she required lower doses of anaesthetic drugs such as propofol and opioid painkillers than patients who heard no music.

That, at least, is what a new peer-reviewed study from Delhi's Maulana Azad Medical College and Lok Nayak Hospital suggests. The research, published in the journal Music and Medicine, offers some of the strongest evidence yet that music played during general anaesthesia can modestly but meaningfully reduce drug requirements and improve recovery.

The study focuses on patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the standard keyhole operation to remove the gallbladder. The procedure is short - usually under an hour - and demands a particularly swift, clear-headed recovery.

To understand why the researchers turned to music, it helps to decode the modern practice of anaesthesia. Our aim is early discharge after surgery, says Dr. Farah Husain, a senior specialist in anaesthesia and certified music therapist for the study. Patients need to wake up clear-headed, alert and oriented, and ideally pain-free. With better pain management, the stress response is curtailed.

Achieving that requires a carefully balanced mix of five or six drugs that together keep the patient asleep, block pain, prevent memory of the surgery and relax the muscles. In procedures like laparoscopic gallbladder removal, anaesthesiologists now often supplement this drug regimen with regional 'blocks' - ultrasound-guided injections that numb nerves in the abdominal wall.

The body does not take to surgery easily. Even under anaesthesia, it reacts: heart rate rises, hormones surge, blood pressure spikes. Reducing and managing this cascade is one of the central goals of modern surgical care. According to Dr. Husain, the stress response can slow recovery and worsen inflammation, highlighting the importance of careful management.

The researchers wanted to know whether music could reduce how much propofol and fentanyl (an opioid painkiller) patients required. Less drugs mean faster awakening, steadier vital signs and reduced side effects. They designed a study involving 56 adults, aged roughly 20 to 45, randomly assigned to two groups. All received the same five-drug regimen; however, only one group heard music through noise-cancelling headphones.

The results were striking: patients exposed to music required lower doses of propofol and fentanyl, experienced smoother recoveries, and had lower cortisol levels. Since the ability to hear remains intact under anaesthesia, the researchers noted, music can still shape the brain's internal state.

Music therapy is not new to medicine; it has long been used in psychiatric care and rehabilitation. However, its entry into the world of anaesthesia marks a shift towards integrating non-pharmacological interventions in surgical settings. As further studies explore music's effects, this research suggests that even simple melodies can facilitate healing, reshaping surgical care and patient experience.

Even as the drugs silence much of her brain, its auditory pathway remains partly active. When she wakes up, she will regain consciousness more quickly and clearly because she required lower doses of anaesthetic drugs such as propofol and opioid painkillers than patients who heard no music.

That, at least, is what a new peer-reviewed study from Delhi's Maulana Azad Medical College and Lok Nayak Hospital suggests. The research, published in the journal Music and Medicine, offers some of the strongest evidence yet that music played during general anaesthesia can modestly but meaningfully reduce drug requirements and improve recovery.

The study focuses on patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the standard keyhole operation to remove the gallbladder. The procedure is short - usually under an hour - and demands a particularly swift, clear-headed recovery.

To understand why the researchers turned to music, it helps to decode the modern practice of anaesthesia. Our aim is early discharge after surgery, says Dr. Farah Husain, a senior specialist in anaesthesia and certified music therapist for the study. Patients need to wake up clear-headed, alert and oriented, and ideally pain-free. With better pain management, the stress response is curtailed.

Achieving that requires a carefully balanced mix of five or six drugs that together keep the patient asleep, block pain, prevent memory of the surgery and relax the muscles. In procedures like laparoscopic gallbladder removal, anaesthesiologists now often supplement this drug regimen with regional 'blocks' - ultrasound-guided injections that numb nerves in the abdominal wall.

The body does not take to surgery easily. Even under anaesthesia, it reacts: heart rate rises, hormones surge, blood pressure spikes. Reducing and managing this cascade is one of the central goals of modern surgical care. According to Dr. Husain, the stress response can slow recovery and worsen inflammation, highlighting the importance of careful management.

The researchers wanted to know whether music could reduce how much propofol and fentanyl (an opioid painkiller) patients required. Less drugs mean faster awakening, steadier vital signs and reduced side effects. They designed a study involving 56 adults, aged roughly 20 to 45, randomly assigned to two groups. All received the same five-drug regimen; however, only one group heard music through noise-cancelling headphones.

The results were striking: patients exposed to music required lower doses of propofol and fentanyl, experienced smoother recoveries, and had lower cortisol levels. Since the ability to hear remains intact under anaesthesia, the researchers noted, music can still shape the brain's internal state.

Music therapy is not new to medicine; it has long been used in psychiatric care and rehabilitation. However, its entry into the world of anaesthesia marks a shift towards integrating non-pharmacological interventions in surgical settings. As further studies explore music's effects, this research suggests that even simple melodies can facilitate healing, reshaping surgical care and patient experience.