A soon as Meri-Tuuli Auer saw the subject line in her junk folder, she knew it was no ordinary spam email. It contained her full name and her social security number - the unique code Finnish people use to access public services and banking.

The email was full of details about Auer no one else should know. The sender knew she had been having psychotherapy through a company called Vastaamo. They said they had hacked into Vastaamo's patient database and that they wanted Auer to pay €200 (£175) in bitcoin within 24 hours, or the price would go up to €500 within 48 hours.

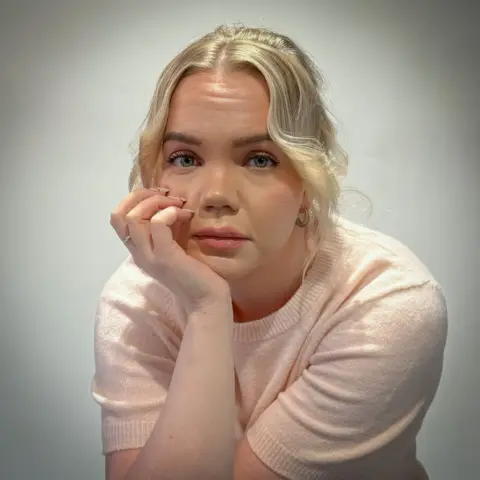

If she did not pay, they wrote, your information will be published for all to see, including your name, address, phone number, social security number and detailed patient records containing transcripts of your conversations with Vastaamo's therapists. That's when the fear set in, Auer, 30, tells me. I took sick leave from work, I closed myself in at home. I didn't want to leave. I didn't want people to see me.

She was one of 33,000 Vastaamo patients held to ransom in October 2020 by a nameless, faceless hacker. They had shared their most intimate thoughts with their therapists including details about suicide attempts, affairs and child sexual abuse.

In Finland, a country of 5.6 million people, everyone seemed to know someone who had their therapy records stolen. It became a national scandal, Finland's biggest-ever crime, and the then Prime Minister Sanna Marin convened an emergency meeting of ministers to discuss a response. But it was already too late to stop the hacker.

Before sending the emails to Vastaamo's patients, the hacker had published the entire database of records stolen from the company on the dark web and an unknown number of people had read or downloaded a copy. These notes have been circulating ever since. Auer had told her therapist things that she didn't even want her closest family members to know - about her binge drinking, and a secret relationship she'd been having with a much older man. Now, her worst fears had come true.

But instead of destroying her, the hack made her realise she was far more resilient than she could have ever imagined. In the months after she learned about the hack, Auer requested a hard copy of her records from Vastaamo. Her notes sit in a thick stack on the table between us as she tells me what happened. Even though their records were released more than five years ago, Vastaamo patients continue to be victimised. Someone has even built a search engine that allows users to find records on the dark web just by typing in a person's name.

The lawyer representing Vastaamo's victims in a civil case against the hacker has told me she knows of at least two cases where people have taken their own lives after learning their therapy notes had been stolen. Auer decided to confront her fears head on. She posted on social media about the hack, letting everyone know that she had been one of the victims. It was a lot easier for me to know that everyone who knew me already knew, she says. She spoke to her family about what was in her leaked records, including the secret relationship she had never told them about before. People were very supportive.

Finally, she chose to take back control of her story by publishing a book about her experiences. Loosely translated, the title is Everyone Gets to Know. I crafted it into a narrative. At least I can tell my side of the story – the one that's not visible in the patient records.

Auer has come to accept that her secrets will always be out there. For my own wellbeing, it's just better not to think about it.\

The email was full of details about Auer no one else should know. The sender knew she had been having psychotherapy through a company called Vastaamo. They said they had hacked into Vastaamo's patient database and that they wanted Auer to pay €200 (£175) in bitcoin within 24 hours, or the price would go up to €500 within 48 hours.

If she did not pay, they wrote, your information will be published for all to see, including your name, address, phone number, social security number and detailed patient records containing transcripts of your conversations with Vastaamo's therapists. That's when the fear set in, Auer, 30, tells me. I took sick leave from work, I closed myself in at home. I didn't want to leave. I didn't want people to see me.

She was one of 33,000 Vastaamo patients held to ransom in October 2020 by a nameless, faceless hacker. They had shared their most intimate thoughts with their therapists including details about suicide attempts, affairs and child sexual abuse.

In Finland, a country of 5.6 million people, everyone seemed to know someone who had their therapy records stolen. It became a national scandal, Finland's biggest-ever crime, and the then Prime Minister Sanna Marin convened an emergency meeting of ministers to discuss a response. But it was already too late to stop the hacker.

Before sending the emails to Vastaamo's patients, the hacker had published the entire database of records stolen from the company on the dark web and an unknown number of people had read or downloaded a copy. These notes have been circulating ever since. Auer had told her therapist things that she didn't even want her closest family members to know - about her binge drinking, and a secret relationship she'd been having with a much older man. Now, her worst fears had come true.

But instead of destroying her, the hack made her realise she was far more resilient than she could have ever imagined. In the months after she learned about the hack, Auer requested a hard copy of her records from Vastaamo. Her notes sit in a thick stack on the table between us as she tells me what happened. Even though their records were released more than five years ago, Vastaamo patients continue to be victimised. Someone has even built a search engine that allows users to find records on the dark web just by typing in a person's name.

The lawyer representing Vastaamo's victims in a civil case against the hacker has told me she knows of at least two cases where people have taken their own lives after learning their therapy notes had been stolen. Auer decided to confront her fears head on. She posted on social media about the hack, letting everyone know that she had been one of the victims. It was a lot easier for me to know that everyone who knew me already knew, she says. She spoke to her family about what was in her leaked records, including the secret relationship she had never told them about before. People were very supportive.

Finally, she chose to take back control of her story by publishing a book about her experiences. Loosely translated, the title is Everyone Gets to Know. I crafted it into a narrative. At least I can tell my side of the story – the one that's not visible in the patient records.

Auer has come to accept that her secrets will always be out there. For my own wellbeing, it's just better not to think about it.\