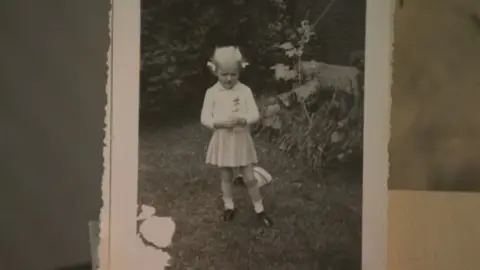

The first thing Lana Ponting remembers about the Allan Memorial Institute, a former psychiatric hospital in Montreal, Canada, is the smell - almost medicinal. 'I didn't like the look of the place. It didn't look like a hospital to me,' she told the BBC from her home in Manitoba. That hospital – once the home of a Scottish shipping magnate – would be her home for a month in April 1958, after a judge ordered the then-16-year-old to undergo treatment for 'disobedient' behaviour.

It was there that Ms Ponting became one of thousands of people experimented on as part of the CIA's top-secret research into mind control. Now, she is one of two named plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit for Canadian victims of the experiments. On Thursday, a judge denied the Royal Victoria Hospital's appeal, paving the way for the lawsuit to proceed.

According to her medical files, which she obtained only recently, Ms Ponting had been running away from home and hanging out with friends her parents disapproved of after a difficult move with her family from Ottawa to Montreal. 'I was an ordinary teenager,' she recalled. But the judge sent her to the Allan.

Once there, she became an unwitting participant in covert CIA experiments known as MK-Ultra. The Cold War project tested the effects of psychedelic drugs like LSD, electroshock treatments and brainwashing techniques on human beings without their consent. Over 100 institutions – hospitals, prisons and schools – in the US and Canada were involved.

At the Allan, McGill University researcher Dr Ewen Cameron drugged patients and made them listen to recordings, sometimes thousands of times, in a process he called 'exploring'. Ms Ponting was subjected to repetitive tape recordings and various drugs as part of these experiments.

The harsh truth about the MK-Ultra experiments first came to light in the 1970s. Since then, several victims have tried to sue the US and Canada. Although lawsuits in the US have largely been unsuccessful, the Canadian government has previously compensated victims without admitting liability.

For decades, Ms Ponting said she felt something was wrong with her, but she did not learn of the details of her own involvement in the experiments until somewhat recently. Now a grandmother, she suffers from lifelong repercussions, including mental-health issues she attributes to her experiences at the Allan. As the lawsuit continues to unfold, she hopes for closure and justice for herself and others affected by these unethical practices.

It was there that Ms Ponting became one of thousands of people experimented on as part of the CIA's top-secret research into mind control. Now, she is one of two named plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit for Canadian victims of the experiments. On Thursday, a judge denied the Royal Victoria Hospital's appeal, paving the way for the lawsuit to proceed.

According to her medical files, which she obtained only recently, Ms Ponting had been running away from home and hanging out with friends her parents disapproved of after a difficult move with her family from Ottawa to Montreal. 'I was an ordinary teenager,' she recalled. But the judge sent her to the Allan.

Once there, she became an unwitting participant in covert CIA experiments known as MK-Ultra. The Cold War project tested the effects of psychedelic drugs like LSD, electroshock treatments and brainwashing techniques on human beings without their consent. Over 100 institutions – hospitals, prisons and schools – in the US and Canada were involved.

At the Allan, McGill University researcher Dr Ewen Cameron drugged patients and made them listen to recordings, sometimes thousands of times, in a process he called 'exploring'. Ms Ponting was subjected to repetitive tape recordings and various drugs as part of these experiments.

The harsh truth about the MK-Ultra experiments first came to light in the 1970s. Since then, several victims have tried to sue the US and Canada. Although lawsuits in the US have largely been unsuccessful, the Canadian government has previously compensated victims without admitting liability.

For decades, Ms Ponting said she felt something was wrong with her, but she did not learn of the details of her own involvement in the experiments until somewhat recently. Now a grandmother, she suffers from lifelong repercussions, including mental-health issues she attributes to her experiences at the Allan. As the lawsuit continues to unfold, she hopes for closure and justice for herself and others affected by these unethical practices.