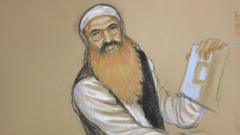

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, faces legal hurdles as the U.S. government attempts to block his planned guilty plea, citing concerns about the integrity of a public trial and capital punishment.

9/11 Mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed's Guilty Plea Blocked by U.S. Government

9/11 Mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed's Guilty Plea Blocked by U.S. Government

The U.S. appeals court intervenes on the eve of Mohamed's guilty plea, aiming to halt previously negotiated deals in a complex legal battle that spans over two decades.

Article Text:

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, known as KSM, once poised to plead guilty to his role in the September 11 terror attacks, saw that opportunity thwarted after the U.S. government moved to block plea deals made last year. Mohammed, held at the Guantanamo Bay military prison for nearly 20 years, was set to appear in a military court when a federal appeals court issued a stay on the proceedings, citing the potential for "irreparable" harm to both the government and the public.

The three-judge panel emphasized that the delay was not an assessment of the case's merits but a necessary step to allow for comprehensive legal arguments to be presented on an expedited basis. This postponement falls into the jurisdiction of the incoming administration, adding another layer of complexity to a case that has dragged on for over two decades.

Initially, Mohammed was expected to admit guilt to multiple charges stemming from the attacks that killed 2,976 people. Having claimed responsibility for the "9/11 operation from A-to-Z," he was set to acknowledge his planning role in the hijackings that devastated the U.S. A series of pre-trial hearings, hampered by ongoing debates about the admissibility of evidence obtained through torture, has contributed to the slow pace of justice in this high-profile case.

In the years following his capture in 2003, Mohammed endured years of harsh treatment at CIA black sites, where he was subjected to waterboarding and other abusive practices. Legal scholar Karen Greenberg argues that this has muddled the possibility of a fair trial under U.S. law, with evidence significantly tainted by the torture inflicted on Mohammed and co-defendants.

A plea agreement struck last summer hinted at potential leniency, including avoiding a death penalty trial, though specifics remained largely undisclosed. His legal representatives had moved forward with the assumption that his guilty plea would lead to a structured public trial where families of 9/11 victims could confront him directly and pose questions about his actions.

However, U.S. officials, including Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, expressed surprise after the plea agreements were arranged, leading to attempts to invalidate the deals as they sought to reaffirm the necessity of holding a public trial. They argued that enforcing the agreements stripped the American public of answers and sentencing possibilities for those responsible for the attacks.

Victims' families exhibit divided reactions to the plea agreements, with some expressing that the arrangement was too lenient while others see it as a potential path to an eventual trial. They are left frustrated by the government's last-minute intervention and the protracted timeline for achieving resolution in the case.

Mohammed continues to be one of the last detainees at Guantanamo, a facility that has long faced scrutiny for its role in the "war on terror." The prison has housed numerous suspects since its establishment after the 9/11 attacks but is now down to 15 detainees, sparking ongoing debates about justice and human rights.

As this saga unfolds, it raises profound questions about the legal system's ability to deliver justice and closure for the victims and their families while navigating the fraught landscape of terrorism, torture, and legal accountability.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, known as KSM, once poised to plead guilty to his role in the September 11 terror attacks, saw that opportunity thwarted after the U.S. government moved to block plea deals made last year. Mohammed, held at the Guantanamo Bay military prison for nearly 20 years, was set to appear in a military court when a federal appeals court issued a stay on the proceedings, citing the potential for "irreparable" harm to both the government and the public.

The three-judge panel emphasized that the delay was not an assessment of the case's merits but a necessary step to allow for comprehensive legal arguments to be presented on an expedited basis. This postponement falls into the jurisdiction of the incoming administration, adding another layer of complexity to a case that has dragged on for over two decades.

Initially, Mohammed was expected to admit guilt to multiple charges stemming from the attacks that killed 2,976 people. Having claimed responsibility for the "9/11 operation from A-to-Z," he was set to acknowledge his planning role in the hijackings that devastated the U.S. A series of pre-trial hearings, hampered by ongoing debates about the admissibility of evidence obtained through torture, has contributed to the slow pace of justice in this high-profile case.

In the years following his capture in 2003, Mohammed endured years of harsh treatment at CIA black sites, where he was subjected to waterboarding and other abusive practices. Legal scholar Karen Greenberg argues that this has muddled the possibility of a fair trial under U.S. law, with evidence significantly tainted by the torture inflicted on Mohammed and co-defendants.

A plea agreement struck last summer hinted at potential leniency, including avoiding a death penalty trial, though specifics remained largely undisclosed. His legal representatives had moved forward with the assumption that his guilty plea would lead to a structured public trial where families of 9/11 victims could confront him directly and pose questions about his actions.

However, U.S. officials, including Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, expressed surprise after the plea agreements were arranged, leading to attempts to invalidate the deals as they sought to reaffirm the necessity of holding a public trial. They argued that enforcing the agreements stripped the American public of answers and sentencing possibilities for those responsible for the attacks.

Victims' families exhibit divided reactions to the plea agreements, with some expressing that the arrangement was too lenient while others see it as a potential path to an eventual trial. They are left frustrated by the government's last-minute intervention and the protracted timeline for achieving resolution in the case.

Mohammed continues to be one of the last detainees at Guantanamo, a facility that has long faced scrutiny for its role in the "war on terror." The prison has housed numerous suspects since its establishment after the 9/11 attacks but is now down to 15 detainees, sparking ongoing debates about justice and human rights.

As this saga unfolds, it raises profound questions about the legal system's ability to deliver justice and closure for the victims and their families while navigating the fraught landscape of terrorism, torture, and legal accountability.